想要趁着周末或公共假期在国内旅游, 但只能想到槟城极乐寺、 吉隆坡双峰塔、 热浪岛, 又觉得这些地方太主流、 人又多、 而且没新鲜感了吗? 今天,小编就要来向大家介绍一些马来西亚可媲美国外、 鲜为人知的冷门景点吧·!

Did You Know You Could Slap Statutes? These “Traitor” Statues in Hangzhou

When travellers think of Hangzhou, they picture misty mornings over West Lake, willow-lined causeways, and poetic scenery that inspired emperors and scholars. But just a short walk from the lake’s quieter northern edge lies one of China’s most unusual historical attractions — a pair of iron statues that generations of visitors have slapped, spat on, and cursed.

These are the kneeling statues of Qin Hui and his wife, figures remembered in Chinese history as symbols of betrayal. Unlike most monuments around the world, these statues were never meant to honour. They were built to shame.

And that’s exactly what they still do.

The historical drama behind the statues

To understand why these statues exist, you need to go back to the 12th century.

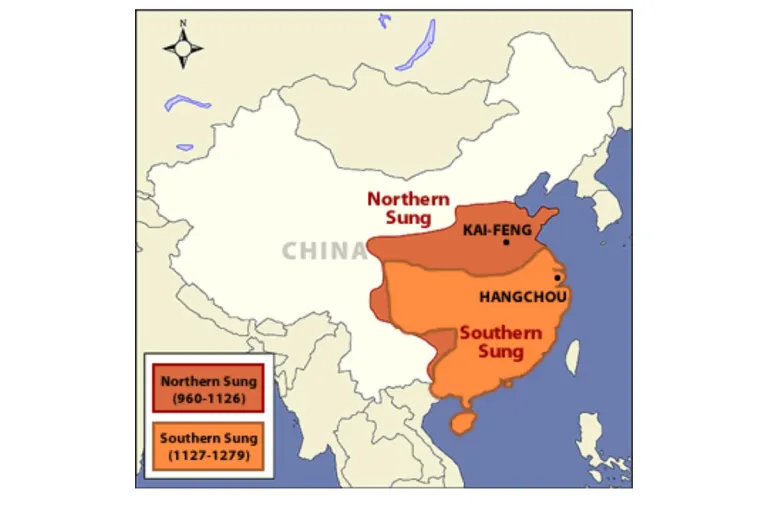

During the Southern Song dynasty, China was politically fractured. The northern territories had fallen to the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty, and the Song court had retreated south. Amid this crisis rose one of China’s most revered military heroes: Yue Fei.

Yue Fei became famous for his military campaigns against the Jin forces. His victories gave hope to a court in exile and to citizens longing to reclaim lost territory. Over time, he came to embody loyalty, patriotism, and moral integrity.

But politics at court told a different story.

Qin Hui, a powerful chief councillor under Emperor Gaozong, advocated for a negotiated peace with the Jin rather than continued warfare. In the traditional narrative passed down for centuries, Qin Hui orchestrated Yue Fei’s recall from the battlefield and framed him on false charges of treason.

In 1142, Yue Fei was executed in prison.

Peace was signed soon after through the Treaty of Shaoxing, formalising the division between north and south. While Qin Hui retained power during his lifetime, history judged him harshly. Yue Fei was later rehabilitated and elevated to near-mythical patriotic status. Qin Hui’s name, meanwhile, became synonymous with treachery.

A monument designed to condemn

Fast forward to the Ming dynasty. Officials in Zhejiang commissioned a memorial complex around Yue Fei’s tomb near West Lake. This became what we now know as the Yue Fei Temple (also called Yuewang Temple).

Here’s where things get unusual.

Rather than simply honouring Yue Fei, the site also included iron statues of Qin Hui, his wife Lady Wang, and other alleged accomplices. The statues were deliberately crafted in humiliating poses:

Kneeling on the ground

Hands bound behind their backs

Ropes around their necks

Heads bowed toward Yue Fei’s tomb

They were originally placed fully exposed in front of the tomb — a permanent display of disgrace.

Unlike statues meant for reverence, these were built as tools of public condemnation. Visitors were expected to see them not as historical curiosities, but as villains deserving scorn.

Yes, people still slap them

For centuries, the public responded exactly as intended.

Records and modern reports indicate that visitors spat on, kicked, cursed, and struck the statues so frequently that they had to be recast multiple times due to damage. Some accounts suggest at least ten replacements over the centuries.

Today, the statues are fenced off to prevent excessive vandalism. But the symbolic ritual remains. Visitors still pose as if slapping them. Some tap the fence in mock blows. Parents bring children to hear the story of loyalty and betrayal.

For many Chinese visitors, the site is not just historical — it’s moral education.

Even food is part of the legend

The story extends beyond the temple grounds.

A popular Chinese breakfast snack, youtiao (fried dough sticks), is widely linked in folklore to Qin Hui and his wife. According to tradition, the two sticks twisted together represent the couple, fried in oil as symbolic punishment for their betrayal.

While historians debate whether this origin story is factual, the association shows how deeply embedded the tale of Yue Fei and Qin Hui is in everyday culture.

What modern travellers can expect

Today, the Yue Fei Temple complex is a well-maintained historical site featuring landscaped gardens, stone carvings, calligraphy panels, and reconstructed halls detailing Yue Fei’s life and military campaigns.

Travellers often highlight several key experiences:

1. A quieter alternative to busy West Lake spots

While West Lake itself can get crowded, the temple grounds are generally calmer, making it a peaceful cultural stop.

2. Strong storytelling appeal

The story of a loyal general betrayed by political intrigue is dramatic and accessible, even for visitors unfamiliar with Song dynasty history.

3. A striking visual contrast

Yue Fei’s dignified tomb and commemorative inscriptions stand in stark contrast to the bound, kneeling statues opposite — a powerful visual narrative of honour versus shame.

However, some travellers note that English explanations are limited. Non-Chinese speakers may benefit from reading about the history beforehand or visiting with a guide.

Plan to spend around 45 minutes to an hour here if you’re including it in a broader West Lake itinerary.

Are there similar statues elsewhere?

Hangzhou’s statues are the most famous, but not the only ones. Several other sites associated with Yue Fei in different provinces have similar kneeling figures of Qin Hui and Lady Wang.

What makes them remarkable isn’t just their existence, but their purpose. Unlike controversial statues in other countries that spark debate over removal, these were created from the outset as condemnatory monuments.

How does this compare globally?

Around the world, statues of controversial figures often become flashpoints.

In Belgium, monuments of King Leopold II have faced vandalism due to his brutal rule over the Congo Free State. In Spain, statues of Francisco Franco have been removed following years of political debate. In South Africa, the statue of Cecil Rhodes was taken down during the “Rhodes Must Fall” movement. In the UK, protesters toppled a statue of Edward Colston into Bristol Harbour.

In many of these cases, societies debate whether controversial monuments should remain standing.

China’s approach with Qin Hui is different. Rather than removing him from public memory, history reshaped him into a permanent warning.

Why this site stands out

What makes the Qin Hui statues so compelling is the inversion of what monuments typically represent.

Statues usually glorify power and prestige. Here, they strip it away. The medium of bronze and iron — normally reserved for heroes — is used to preserve disgrace.

For travellers, especially those from Southeast Asia where debates over historical memory also surface from time to time, the site offers a fascinating case study in how collective memory is shaped. It’s not just about scenic beauty or ancient architecture. It’s about how societies decide who to honour — and who to condemn.

Walking past Yue Fei’s restored tomb and facing the kneeling figures opposite, you can feel the emotional weight embedded in the landscape. Eight centuries later, the story still provokes reaction.

And perhaps that’s the real reason people still line up to slap the statues.

They aren’t just touching metal.

They’re participating in history.

Published on

About Author

RECOMMENDED READS

本地旅游好好玩! 马来西亚 10个 2025 必游的仙境 【Pulau Langkawi爆红住宿TOP 8】超高颜值的酒店,照片请来一波! 9月16日。。。约吗?

【亚洲跨年烟花TOP 8】带上家人和另一半欣赏爆炸式的浪漫! 每年的跨年大集会, 除了有歌舞升平的好气象之外, 还会有各种烟花大会, 迎接2020的到来~ 为你推荐这些超吸睛的烟火会, 还不赶快带上你最亲爱的去欣赏这份免费的浪漫情怀?!

【冬季篇】日本必去打卡的秘境TOP 10✅ 日本, 是亚洲一个神奇的旅游胜地。 但凡去过一次, 就会上瘾, 然后就会想要探索那里的春夏秋冬。 日本的冬季, 可以达到零下的温度, 甚至有很多越冷越受欢迎的景点。值得一提的是, 日本的冬季集浪漫、 萧条、 迷人为一身。 你也可以趁着冬季来到北海道滑雪, 或是泡一个美美的温泉! 无以伦比的旅行就此开始。

【印尼•棉蘭】5D4N 玩轉Medan行程花費 大家都在问,棉蘭有什麼好玩?世界上最大的火山湖Lake Toba 还有亞洲最活躍火山之Sibayak都在那里!

RECENT ARTICLES

中国的“你死了吗?”App:对全球孤独危机最直白的数码回应 一款名字毫不避讳、每天提醒用户“报平安”的中国App爆红,也揭开了远超中国国界的孤独危机

Romantic 3D2N Getaways for Busy Malaysian Couples Short-haul romantic escapes that fit perfectly into a long weekend.

8 Fine Dining Spots in KL Perfect for Special Occasions From skyline views to chef’s tables, these fine dining spots in KL are made for unforgettable celebrations.

8 Best Nasi Lemak Spots in Klang Valley, From Classic Stalls to Modern Bowls These are Klang Valley’s standout nasi lemak stops.

Ipoh Food Guide: 8 Must-Try Local Spots Beyond White Coffee Skip the clichés — these kopitiams, noodle shops and supper streets show why Ipoh is a true food city.